Market Lemmings Case Study: Tourmaline Oil Corp.

June 18, 2015 1 Comment

The fall in oil prices is starting to expose some of the waste in the energy sector, but this central bank fueled bubble is still rife with clusters of error.

The ‘boom’ phase of the business cycle — more accurately described as the malinvestment phase — is where a lot of things just stop making sense. People will shovel money into wasteful investments based on distorted credit conditions and hyped up expectations.

Today our case study is Tourmaline Oil Corp., a favorite in the independent energy growth company category. With a 52-week high of $58.73, the consensus analyst rating is “buy” while presently trading around $39 at 18x earnings. It recently issued $168 million in new shares (at $39.50/share).

CMR analyst Daniel Plainview shows why Tourmaline is an economic black hole relying on the “greater fool.” Regardless of whatever distortions manifest in the stock market, Tourmaline is its present form is a zombie company — not an investment, but just one of many ways to gamble in the stock market casino.

A Question for Tourmaline Oil Corp.: How Do You Make Money?

By Daniel Plainview

When trying to determine the proper price of a stock the conventional rule of thumb is to predict the amount of money that stock is going to make each year over the long term, and then discount those earnings to the present at an appropriate rate for the risk you are taking.

The inverse of this, but it is in essence the exact same methodology, is to use a Price to Earnings ratio to evaluate a stock. The higher the ratio, the more expensive the stock; the lower the ratio, the more likely you are getting a good deal, so long as the future earnings hold up.

But what if the stock you are looking at is in an industry that typically doesn’t make any money? I’m referring to industries where the company earnings are often affected, to a large degree, by depletion expenses.

Depletion is a non-cash charge and it can ensure that a company generates plenty of cash flow but renders the conventional Price to Earnings analysis moot. Industries with high DD&A (Depletion, Depreciation & Amortization) are generally involved in resource extraction.

Because earnings are essentially meaningless for a lot of resource companies (not to mention the other accounting tricks that can affect earnings) it’s always a good idea to look at a company’s cash flows. There are three types of cash flows:

- Cash flows from operations

- Cash flows from investing

- Cash flow from financing

While in any given period the cash flows in any of these buckets can be either positive or negative, over the medium to longer term (2+ years) one invariably wants to see that cash flow from operations is positive, cash flows from investing is slightly negative, and cash flows from financing is also negative; with the change in cash position from period to period being immaterial.

What a positive/negative/negative cash flow segmentation is indicative of is 1) the company is making money, 2) that it is reinvesting in the business to grow the business, and 3) it is able to return capital to the shareholder, or at least doesn’t steadily require new financing to fund its investments.

It is with this in mind that we now consider the Canadian oil and gas industry.

Recently the commodity prices that drive the cash flow from operations that Exploration and Production (E&P) companies generate took a tumble. Both oil and gas prices fell by ~50% from their levels in the first half of 2014.

By itself a single year of lousy prices shouldn’t erode as much value in the markets as what occurred, but what changed is the market is now more pessimistic about prices for all future periods too.

Companies have responded by scaling back their investing, and cutting capital expenditures for the drilling of new wells and building of new facilities.

Generally speaking, oil and gas companies always have to be spending some money on new production in order to maintain overall production levels. Well performance declines over time, and by how much depends a lot on the geology of the particular “play”.

A really good well might only decline at ~20% per year, but it still declines. Newer unconventional extraction methods (drilling horizontal multi-stage frac wells into shales) can come down a lot faster: ~50% per year.

So ultimately the goal of any oil and gas company, in any environment, is to have enough cash flow from operations that it can pay for all the cash flow from investing (capital expenditures needed to keep production up), and still have enough left over to pay the shareholder.

Enter Tourmaline Oil: the oil company that has 85% of their production coming from natural gas. Etymology aside, there are more serious issues with this company’s business model.

In their last earnings announcement in March, they happily proclaimed their 76% growth in cash flow. Sounds good… but wait! There is a footnote: “Cash flow is defined as cash provided by operations before changes in non-cash operating working capital.” So what about capital expenditures?

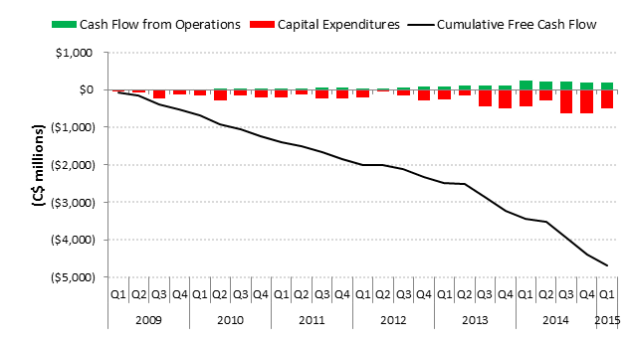

The cash flow from operations is in green, and the company’s capital expenditures (only a sub-set of cash flow from investing) are in red. The black line represents the cumulative amount of cash flow from operations minus capital expenditures (or Free Cash Flow) up to each period.

What this shows is that Tourmaline has spent almost $4.7 billion more on drilling holes in the ground, than it has made from the hydrocarbons those holes have produced, since 2009. Furthermore, over 25 quarters of results, they have never made more money than they spent: Free Cash Flow has never been positive.

In the company’s defense, they have grown production at an industry-leading rate. But it really looks like they’re spending a dollar to make fifty cents, and making up for it on volume.

It has gotten to the point where if the company stopped spending money, but continued to earn cash flow from operations (and let us assume the same prices and only a 20% production annual decline), they could not make that money back. In actuality Tourmaline’s wells probably decline a lot harder than 20%, but the story is bad enough as it is.

These harsh realities force us to ask the question: where did the company get $4.7 billion? The answer is that they got it from new investors who bought shares in secondary offerings, and some money from raising debt. It looks as though this external funding process will have to continue ad infinitum; another secondary offering being announced just recently for $168 million.

And investors should keep this in mind: the only reason Tourmaline is able to grow production on a per share basis is because the shares have a decent valuation, but the only reason the shares manage to eke out a decent valuation is because they are able to grow production on a per share basis. If the shares were to fall enough in price, the amount of dilution created by external financing would make it impossible for the company to grow.

And the last point to make about the company: the management team in prior iterations at Berkeley and at Duvernay were able to successfully build up and then sell the company to a bigger fish. Duvernay in particular made a lot of people a lot of money as it was sold at the height of the commodity boom in 2008 and Shell paid an unmatched valuation in the transaction (~27x EBITDA).

In fact, the only way Tourmaline’s business model makes any sense is with an M&A exit strategy: ramp up production at any price, and find a sucker to buy it just before the house of cards collapses.

But if investors are assuming Tourmaline will be similarly sold I would only point out that Tourmaline is now worth about $9.2 billion and is the 8th largest E&P company by market capitalization in Canada. It’s getting to be too big for others to swallow, and suckers like Shell might be hard to find this time around.

Then again, they did just find another 4.25 million suckers…

(Click here for supporting calculations.)

Pingback: A Bleak Update on Tourmaline Oil Corp. (TOU) | CANADIAN MARKET REVIEW